How Italy and New York shaped banking

The story unfolds in the archives of Intesa Sanpaolo

10/04/2018

If there is one city that encapsulates Intesa Sanpaolo’s evolution outside Italy, it has to be New York. Almost all the banks that joined the group over the years had a presence in the Big Apple at some point.

It all began with remittances. At the turn of the last century, communities such as Little Italy in New York were beginning to make their economic mark. “The most important factor at the outset was the focus on Italian migrants and the emergence of numerous Italian colonies in the Americas. That is what took banks into the United States,” says Barbara Costa, head of Intesa Sanpaolo’s historical archives.

The New York Post Office estimates that between 1901 and 1906, around 12.3m individual money orders were sent to foreign countries, with half of the dollar amounts going to Italy, Hungary and Slavic countries. According to the Immigration Commission, the sum of remittances to Italy in 1907 amounted to $85m (more than $2bn today).

Banca Commerciale Italiana, New York: One William Street branch, 1980-1984 (unknown photographer)

“The most amazing investments that happen here are sometimes in industries that are almost dead. An investor opens a local factory, gets into the value chain of the Japanese or Koreans and starts producing high volumes. The same things that Italian companies do for German companies can happen here producing for Japanese and Korean big brands,” he adds. “The investment does not need to be large, and it is anyway a lot cheaper than in Europe”

To take advantage, companies must be present in the country – both in terms of production and in person. For those looking to get into the sort of business the Japanese and Koreans are offering, having a product that is made in Vietnam and readily available for buyers, as well as a senior team on the ground, is essential.

Not being there or coming only when necessary can be catastrophic. Andreatta recalls a horror story of a $100 million deal being lost because an elderly entrepreneur with a backache chose to send a representative to a key meeting rather than attend himself.

Andreatta says the companies that today most benefit from exporting from Italy are those in top luxury goods. An emerging middle class in the cities of Vietnam – with a taste for all things Italian – is yet another space for Italian businesses to move into.

“The local market is becoming more and more affluent and people in the cities have a penchant for Italy. They like the fact that goods are Italian,” he says.

The Vietnam bureau also provides financing for multinationals operating in the region – at Italian levels of risk. With Intesa Sanpaolo’s long-standing commitment to the development of the circular economy in mind, Andreatta says that the big opportunities for multinationals are in greening the country – reforming the energy industry, for instance.

“Vietnam is blessed with a lot of sun and wind, so everything needed for the creation of green energy is there. At the moment it uses more electricity than other countries. The opportunity for energy efficiency is enormous,” he says.

Additionally, Vietnam has a plastics problem. It is the world’s fourth-largest plastic polluter of the ocean, largely because huge volumes of plastic are exported from Europe for recycling. The country has no infrastructure to deal with this.

Banca Commerciale Italiana, New York: One William Street branch, 1984 (picture by Jay Maisel)

Costa highlights how the banks had to adapt to the local environment as their operations expanded. “American law limited the activities that foreign-owned bank branches could perform. This affected the deposits of Italian emigrant communities. The Italian banks had to start trust companies to be on a par with their American counterparts,” she says. BCI’s Italian Commercial Bank Trust Company opened in New York in 1924 while the Bank of Naples Trust Company followed in 1929.

Although the Wall Street Crash in 1929 had an impact on Italian banks, this was more because of a crisis in world banking and financial systems rather than local pressures. The real crunch came with the Second World War, when all the assets of Italian branches in the US were seized and the banks themselves liquidated. The director of the New York branch of BCI, Guglielmo Reiss Romoli, was interned in Ellis Island prison until his return to Italy in 1942.

The Italian banks hurried back at the end of the war to occupy the places they had been forced to abandon. BCI’s long-serving managing director, Raffaele Mattioli, was part of the first post-Fascist Italian economic mission to the United States between November 1944 and March 1945. The bank opened a representative office in New York in 1946 and set about re-establishing relations with the American financial and business world. Banco di Napoli had already opened its representative office in 1945 and transferred into an agency in 1950.

Comit Trust Co., New York: Harlem agency, 2nd Avenue and 116th Street, 1930-1931 (unknown photographer)

Back home, banks were thriving as post-war Italy entered a period of strong economic growth during the Sixties. Inevitably they started to widen their horizons. “From the Seventies onwards, Italian banks were looking to form alliances and expand their presences abroad to boost their competitiveness in the face of large multinational banks, especially those in North America,” Costa observes.

New York’s financial centre became indispensable for smaller institutions and many of those destined to become part of Intesa Sanpaolo set up offices in New York during the period: Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (1975), Banco Ambrosiano (1976), Cariplo (1979) and Istituto Bancario San Paolo (1980).

However, this expansionary phase did not last long. By the nineties, consolidation in international banking was under way. It led to significant restructuring of networks and changes in the way they operated in Italy and abroad. There were closures, licensing partnerships were ended and shareholdings were sold during a period of intense restructuring. But there were also new openings and a transformation of the types of operations that Italian banks performed, creating a new international perspective.

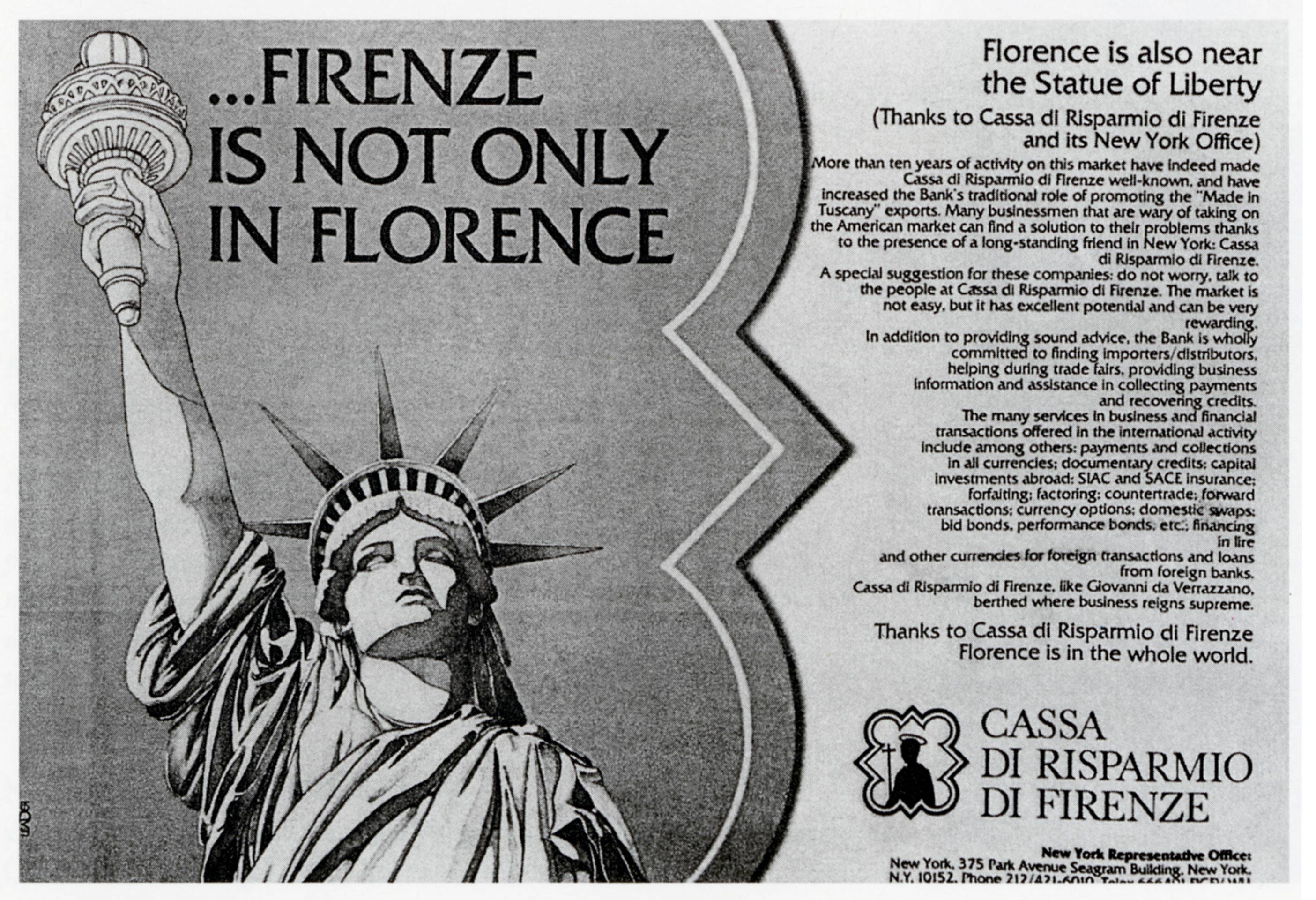

Cassa di risparmio di Firenze, advertising bank’s presence in New York, 1985

Many of the banks may have left New York, but the buildings they occupied remain. BCI has the most significant heritage in the city. Its first home was 65 Broadway, in a building that later became the headquarters of American Express until 1975. Today, Intesa Sanpaolo’s offices are in the 1 William Street building in the financial district of Lower Manhattan. Once the headquarters of the investment bank Lehman Brothers, it has now been renamed the Banca Commerciale Italiana Building.

BCI, New York: One William Street branch, 30 December 1982 (photo by Santi Visalli)

Tracing the operations of Intesa Sanpaolo’s banks across the world would be impossible without the firm’s historical archives. Costa highlights the parts that provide information about New York: “There is considerable documentation about openings of branches and representative offices in the city, what happened at the outbreak of war and Mattioli’s trip at the end of the conflict,” she explains.

The banks’ individual house journals and corporate bulletins provide invaluable inside views of how the financial institutions worked. The archives contain a wealth of images not only of the buildings, but also of the people who worked in them and the advertising they used to market products and services.